The following is a very general overview of patenting. Because it is only general, and not intended to apply to any specific situation, consult with me or another competent patent attorney before relying on this overview.

Generally, a patent is a written document that:

Fundamentally, a patent applicant must sacrifice the secrecy of their innovative concept to receive limited patent rights, i.e., the rights to exclude others from exploiting that concept by making, importing, using, offering for sale, or selling products or processes that implement that concept in the country that issued the patent. But not every patent application results in a patent, meaning that sometimes the applicant forfeits the secrecy of their innovation and receives nothing in exchange. Due to that risk, filing a patent application is more like taking a bet that the secret is sufficiently innovative, and the patent application is written sufficiently well, that loss of secrecy will be well-rewarded.

Innovators see and seek patents as tools for protecting their substantial investments, such as in research, product development, manufacturing, marketing, and customer relations, by discouraging competitors from introducing products that implement the innovative concept, or at least forcing competitors to agree to a (typically paid) license to do so.

Most governments grant patents to encourage detailed and improvement-empowering written descriptions of innovative concepts to the public, thereby continually increasing the public’s knowledge base and the evolution of still more innovations. Although granted patent rights can provide a powerful incentive to researching and developing innovations, they are of limited duration, and typically expire within 20 years of the filing of an application for the patent.

Except as noted, this discussion will focus on U.S. patents.

In the U.S., there are three basic categories of patent applications:

Because the Utility category is by far the largest (roughly 90% of all U.S. patent applications), it is the primary focus of my communications and is implied whenever the word “patent” alone is used.

The Utility category includes two types of applications:

The range of innovative concepts that are eligible for patenting via U.S. is incredibly wide, including nearly anything that involves or results from a human-caused transformation and is reasonably categorized within any of these 4 broad classes:

Within these 4 broad classes of innovative concepts, the USPTO is required to grant/issue a utility patent on a non-provisional patent application that adequately describes how to implement what the law refers to as “useful”, “novel”, and “non-obvious” “subject matter” ((i.e., a “concept”) that is properly claimed.

Useful

Under the patent laws, a claimed concept is not considered sufficiently useful if it is merely a law of nature, a physical phenomenon, or too abstract (has no described real world implementations). Also, the patent application must identify a beneficial use for the claimed concept (other than acting as, for example, a boat anchor, paperweight, or research curiosity). Note that something that is patentably useful is said to provide “utility” (and thus evokes the phrase “utility patent”).

Novel

For a claimed concept to be patentable, it must be new to the world, i.e., “novel”. While seemingly a simple notion, as with many topics in patent law, novelty has considerable complexities, which will be explained in greater detail a bit further ahead. But for the moment, let’s start with three basic general understandings (each of which has some important exceptions).

First, the date one files an initial patent application that properly describes how to implement a concept is the “filing date” of that application. Crucially, that date also is the “effective filing date” of any properly presented claim to that concept.

The importance of an effective filing date is that it defines what qualifies as “prior art” that can be used to challenge the patentability of a claim. In this context, “art” surprisingly means the technical realm of the innovative concept. Consequently, “prior art” is everything in the world that was publicly known in that realm prior to the concept’s effective filing date. Speaking generally, a claimed concept is not novel if a single item of prior art “teaches” (i.e., describes how to make and use) the entirety of that concept.

Because one never knows when another party might create close prior art, obtaining the earliest possible effective filing date might be vital.

Prior art can be created by others by, for example, their publishing a description of their independently developed version of your company’s innovative concept, presenting their version of the concept at a conference, or selling a product that implements the concept. As an aspiring owner to a patent containing at least one claim that covers the innovative concept, you want other’s uncomfortably close versions of that concept to be made public after, rather than before, your claim’s effective filing date so that their public disclosure of the concept won’t qualify as prior art that can be used to defeat the patentability of your claim (and so that if you earn the patent, they might have to obtain your permission to continue implementing the concept without incurring liability for infringement of your claim).

Second, a claimed concept is not permitted to be patented when another U.S. patent application (that does not have the same inventors) describes the same concept, has an earlier effective filing date, and is eventually published. In other words, between two competing applicants for the same concept, the applicant who files their properly-written application with the USPTO first typically wins the race for a patent on the concept.

Third, and as hinted above, in addition to publications and patent applications, many other things can qualify as novelty-defeating prior art, including public speeches, presentations, displays, demonstrations, and uses, and even commercialization activities such as offers for sale and sales.

Non-obvious

Shifting gears, a claimed concept is considered legally obvious if, as of its effective filing date, a person having ordinary skill in the art would have known of art-recognized reasons to modify or combine relevant prior art references (considered as a whole), and would have had a reasonable expectation of success that in doing so they would to arrive at the entirety of that claimed concept. Thus, although a layperson or engineer might exclaim that a claimed concept seems “obvious” (typically because, after reading the claim, they can understand how the concept works or can predict that it likely will work), U.S. patent law can be rather strict about what must be proven before that claimed concept will be deemed “obvious” from a legal perspective.

A Patentability Search often can help reveal whether a concept lacks novelty (and sometimes whether it is obvious).

Described

Finally, for a concept to be patentable, its application must properly describe how to implement that concept. Generally, a patent application’s description of a claimed concept is considered legally adequate if, as of the application’s effective filing date, that description would have empowered a person having ordinary skill in the art to implement that concept, and reasonably demonstrates that the innovators actually had that concept in mind.

Generally, design patents protect ornamental (i.e., aesthetic and non-functional), novel, non-obvious features of a product, as graphically described in an enabling manner (that is, sufficient to describe to a person having ordinary skill in the art what that ornamental feature looks like).

Unlike utility patents, which generally have a term of 20 years from their application’s effective filing date, design patents expire 15 years after they are issued and do not require the payment of Maintenance Fees.

Also, provisional patent applications are not available for design patents.

Design patents tend to issue without lengthy prosecution. Thus, design patents usually are much less expensive to obtain than utility patents.

Lastly, design patents can be invalidated if the design has a substantial non-aesthetic function or a practical utility.

There are numerous potential rewards associated with the patenting process, particularly for those who pursue that process well.

Traditionally, a patent can be utilized for:

2. Creating and enhancing revenue, such as by::

3. Distinguishing inventors and owners, such as by:

Of course, a patent rights only arise upon issuance of a patent. No patent means no patent rights. Thus, only an issued patent can be legally enforced against potential and/or actual competitors to prevent the making, using, offering for sale, and/or selling in, and/or importing into, the country in which the patent is in force, anything that falls within the scope of one or more valid unexpired claims of that patent.

Most competitors would rather not be dragged into a patent infringement lawsuit that might distract their company for years and cost them tremendous sums in legal fees alone. It’s that fear of litigation that typically creates the most power and value for the patent owner, because it forces competitors to compete on the patent owner’s terms. That is, in the face of a strong patent, to avoid legal liability a competitor must offer inferior products to their customers, try to design-around the patented concepts, and/or pay license fees to the patent’s owner in exchange for offering those customer-demanded concepts in their products.

Fortunately for patent owners, the power and value of their patents often can be harnessed without even mentioning the word “suit” to a competitor. For example, enforcement often can be achieved inexpensively outside the judicial system, such as via providing a simple “Patent Pending” notice on the patent owner’s goods that fall within the scope of one or more claims of an unexpired in-force patent.

Turning up the heat somewhat, enforcement occasionally can require the patent owner to inform an infringing competitor of the relevant patent(s). Often, the patent owner is willing to allow competitors to make, use, and/or sell their patented concept, provided that the competitors pay the patent owner fairly for the right to do so. A document that specifies such rights and the associated payments to the patent owner is typically called a “Licensing Agreement”.

If the offer of a license to an apparently infringing competitor is refused, the patent owner might need to file a lawsuit alleging infringement of the patent. If the parties are unable to settle their differences early in the suit, the litigation costs can become very expensive and time-consuming for both parties. Fortunately, those costs inspire the vast majority of patent infringement suits to settle rather quickly.

Those who do not have the financial means to enforce a patent in court often can much more affordably purchase patent assertion insurance that will provide the financial muscle to litigate all the way to an enforceable court judgment, even after being upheld on appeal, if necessary.

Alternatively, third-party litigation funders support a substantial portion of all patent infringement litigation today.

No matter how much money any company spends or what degree of professional assistance it obtains, the potential risks associated with the patenting process are substantial and should be carefully considered before and while pursuing that process.

Although most of these risks can be managed, it can be very difficult to predict with any reasonable accuracy, for example, how the USPTO will respond to a given patent application, how much time or effort will be needed to convince the USPTO to issue a patent, or what the scope of the claims of the issued patent will be.

And even if a patent examiner asserts an illegal or factually unsupported position, there is no valid guarantee that efforts to overcome that position will necessarily be successful, or that the desired patent will result. Further, obtaining issuance of a patent is no guarantee of freedom to operate (i.e., non-infringement of other’s patent claims).

Similarly, there are no certainties as to, for example, how the market will react to an innovative concept, whether a company will be able to successfully license or enforce its patent, and/or whether the company will obtain a reasonable return on its investment in the patenting process.

These and other potential risks associated with the innovation and patenting processes are significant and should be considered before and while pursuing those processes.

Utilizing the services of a competent patent attorney often can help lessen some of these risks, but not all these risks can be eliminated entirely. When it comes down to it, as with most investments, pursuing patent protection is always a gamble.

Thus, it is important that your company recognizes, weighs, and maintains realistic expectations of the potential costs, potential benefits, and potential risks, both throughout the innovation and patenting processes and beyond.

Although other forms of protection should always be at least briefly considered to supplement patent protection, patenting is not the best approach in certain situations. For example, sometimes it is more advantageous to:

For example, relying on trade secrecy can be the best approach when:

If speedy protection is needed, particularly from copy-cat pirates, then initially obtaining design patent protection of a product’s ornamental features might make more sense than waiting possibly years for a utility patent to issue that protects the product’s functional features. And keep in mind that, compared to utility patents, enforcing design patents can be much quicker and cheaper too. On the flip side, design patents can be much easier for a competitor to successfully “design around”, so typically they are most useful only against rather blatant knockoffs.

On occasion, a company can land a valuable supplier agreement that, for example, locks-out competitors from access to a critical material, component, or service, provides very favorable long-term pricing, and/or secures other highly beneficial terms (involving, e.g., features, financing, inventory management, delivery, co-marketing, service, warranty, indemnity, etc.). The possibilities here are nearly endless, and occasionally can provide even stronger leverage than patenting.

Branding and/or marketing techniques sometimes can be more effective than patenting, particularly where tremendously strong goodwill is generated and can be maintained for a brand. Generating such strong goodwill usually requires a substantial and sustained investment. Maintaining that goodwill often mandates careful and highly responsive brand management, given that events can rapidly arise that tarnish a brand, thereby quickly eroding the goodwill and undermining the corresponding investment in that brand.

The general process for obtaining a valuable patent is:

I help my clients with each of these steps of the patenting process.

Because I am authorized to practice law only in the United States, this discussion centers on obtaining a U.S. patent. I am happy to discuss my U.S. capabilities, and how I can aid in obtaining a patent in foreign countries via my network of foreign patent professionals.

This is a very general overview of patenting. Because it is only general, and not intended to apply to any specific situation, consult with me or another competent patent attorney before relying on this explanation.

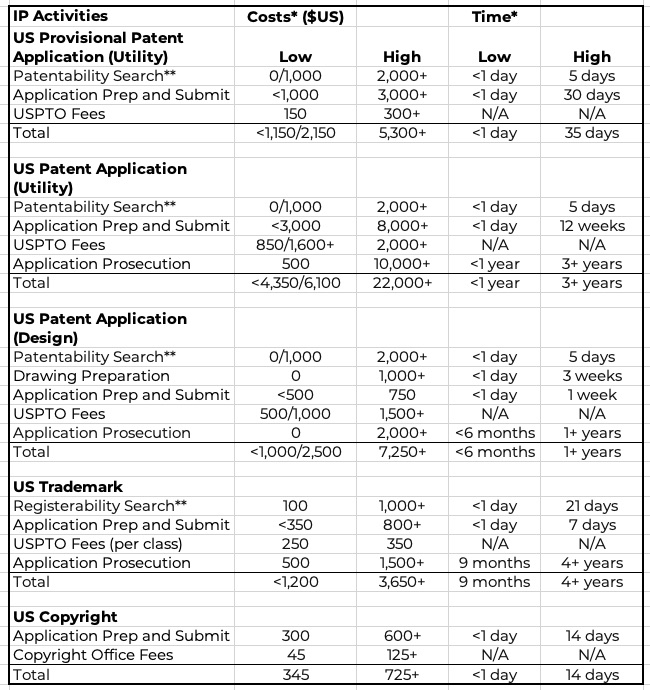

From the perspective of most individuals, (utility) patents are relatively expensive to obtain and maintain. For example, as of late 2023, by the time the USPTO issues a U.S. patent, the average applicant will have spent a total of at least $15,000 (and possibly considerably more) on the costs of preparing, filing, and, although somewhat deferred, prosecuting the underlying non-provisional U.S. patent application. The costs in most countries foreign to the U.S. can be less, but in some cases are greater (particularly when translations to and from English are needed). Fortunately, a substantial portion of these costs (i.e., the prosecution costs) can be deferred until after the patent application is prepared and filed. I would be glad to discuss ways to manage these and all patent-related costs.

Also, I am dedicated to avoiding unnecessary overhead and keep my fees very competitive.

Currently, I usually charge $360 per hour. Whenever appropriate, I utilize highly-experienced and well-supervised patent agents, typically billed at $150 – $200 per hour; paralegals, typically at $180 per hour, and/or patent law clerks, typically at $100 – $125 per hour.

A full list of the USPTO’s fees can be accessed here.

Also, I carefully manage my commitments to avoid becoming overloaded, and, when necessary, engage additional highly competent professionals.

Based on my experiences, the cost and timing ranges listed in the following table are not unusual for the listed IP protection activities:

* Very common activities only for single invention, mark, class, or work. Does not include counseling, opinions, exceptional needs, or certain potential expenses, such as translation costs, formal drawings, express mail, travel, or extension, appeal, or maintenance fees. Keep in mind that expenses, the amount of attorney time required, and provider availability can vary widely depending on the specifics of a particular situation, and thus total costs and durations could differ significantly from these ranges. Do not rely on these cost or timing ranges without speaking to me about your particular situation.

**Although searches are generally recommended, they might not be advised in certain situations.

Many countries outright forbid patenting of a concept if there is any public disclosure (and sometimes any attempt at commercialization) of that concept before the filing of a patent application.

So generally, the patenting process truly encourages a “race to the patent office” to protect innovative concepts.

Consequently, if your company wants to preserve its right to file a patent application outside the U.S. (and potentially within the U.S.), I generally recommend the filing of at least a well-written provisional patent application (and preferably a non-provisional) before any disclosure, offer for sale, or commercialization of the innovation occurs.

Speaking of provisionals, recall that a U.S. non-provisional seeking to benefit from the submission of a U.S. provisional patent application must be filed within 12 months of the filing date of that provisional.

Once an initial patent application is filed in most countries (including the U.S.), any desired corresponding foreign or international patent applications must be filed within 1 year.

For example, if I file a patent application in the U.S. and later decide to file that same application in Japan, I must do so within 1 year of the filing date of the U.S. application.

Before making a substantial investment in a patent application, it almost always will be helpful to obtain a professional patentability search. These searches will attempt to identify pre-existing (“prior art”) publications that describe most or all the major features of the innovative concept, thereby potentially showing that the concept is not new or inventive. A basic pre-filing version of such a search typically can be completed within 1 to 10 days, and usually costs between $1500 and $2500. A basic search can identify certain relevant publications and can help one avoid wasting money trying to patent an unpatentable concept.

The decision to seek a patent should be thoroughly and carefully considered. The patenting process can be expensive, lengthy, and risky, not to mention frustrating at times. Yet, the rewards can be substantial.

Generally, one should seek a patent if the expected risk-adjusted return justifies the investment in the patent. For some, merely having their name on a patent, or a patent number on their product, is incredibly valuable, particularly when marketing their capabilities to potential investors, customers, employees, etc.

For others, the opportunity to obtain royalties or other forms of licensing revenue from those who wish to manufacture, use, sell, and/or distribute the patented product is an ample justification to pursue patenting.

For still others, the right to exclude competitors from making, using, importing, offering for sale, or selling the patented innovation can provide a sufficient reward for their investment in obtaining the patent.

And of course, patents are frequently used as “trading cards” for empowering deals of all sorts between patent owners and suppliers, customers, current competitors, litigation opponents of competitors, potential market entrants, etc.

Despite the beckoning of these potential benefits, recognize that the patent process is moderately risky. For example, not all patent applications result in issued patents, though on a hopeful note, the USPTO’s patent grant rate has substantially increased in the last few years. Although the percentage varies from year-to-year, roughly 75% of original patent applications are eventually granted, while the remaining patent applications are abandoned, with their subject matter potentially dedicated to the public domain. Keep in mind that this abandonment percentage includes all original patent applications, including:

Thus, when sufficient resources are properly applied, the likelihood of success with the patenting process can be greatly improved with respect to this 75% metric. Generally, the better the patentability search, the better the preparation of the patent application. Likewise, typically the better the prosecution of that application, the greater the odds are that the application will be issued, assuming the applicant remains committed to obtaining that patent. Similarly, the better the business plan, and the better the implementation of that plan, the greater the likelihood that a substantial return will be earned on the issued patent.

Applying appropriate patent valuation techniques, we can work with you to determine potential returns, investments, and risks, along with the likely timings of each of those financial events. With that information in hand, an appropriate business plan can be developed for obtaining the optimal return on your company’s patent investment.

“Invention Promoters” are also sometimes known as “Invention Marketers” and “Invention Brokers”. In addition to preparing and filing patent applications that usually have extremely narrow and worthless claims, Invention Promoters typically offer to:

Too often, however, customers of Invention Promoters have reported paying substantial sums while receiving remarkably little service in exchange. These unscrupulous Invention Promoters are generally known for high-pressure sales techniques, repeated misrepresentations, and even downright fraud.

Because so many innovators had endured so many ugly experiences at the hands of Invention Promoters, in 1999 Congress enacted section 297 of the Patent Act (35 U.S. C. 1 et seq.), which provides substantial legal remedies for customers found by a court to have been injured by an Invention Promoter.

The USPTO publishes warning signs and suggestions for dealing with Invention Promoters and posts complaints about Invention Promoters. See: http://www.uspto.gov/inventors/scam_prevention/index.jsp

The Federal Trade Commission also provides alerts and tips for avoiding problems with Invention Promoters. See: https://consumer.ftc.gov/articles/invention-promotion-scams

Typically, Invention Promoters are not patent attorneys, licensed to practice law, or registered with the USPTO.

On the other hand, a registered patent attorney will be legally permitted to prepare and prosecute patent applications, draft agreements, and provide legal advice. Although your company’s patent attorney’s primary focus probably will not be on raising capital, developing products, marketing innovations, etc., they will have provided basic legal guidance in these areas, and be able to identify reputable professionals and resources to assist with your needs.

In other words, can you “patent it” yourself?

Yes, you certainly can. It is legally permissible for anyone to write, file, and prosecute a patent application for their innovation with no professional assistance.

But just as with performing your own brain surgery or flying your own space shuttle, rarely is it advisable to enter such difficult waters without relying on substantial help from a well-trained and deeply experienced professional.

What makes patenting so difficult? For starters, there are the labyrinthine federal statutes and rules, along with thousands of court cases interpreting those laws, as well as the MPEP, a roughly 6-inch-thick (if printed) set of administrative procedures promulgated by the USPTO.

Moreover, the courts, and particularly the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears nearly all patent appeals (and for nearly all practical purposes decides which litigated patents have teeth and which are toothless), have changed directions repeatedly over the last few decades in their interpretation of the patent laws, to such an extreme degree that even many patent attorneys have trouble keeping up.

Finally, if they give your company any attention at all, those who might otherwise be appropriate candidates to license your company’s patent will lick their chops at the thought of taking advantage of your company when they realize it obtained its patent without competent legal representation.

Savvy investors will nearly always decline the opportunity to invest in a startup that patented their innovative concept without professional help. It’s almost a certainty that the resulting patent is toothless due to its claims being invalid, unlikely to be infringed, or easy to design around, thereby widely opening the doors for competitors to freely implement the innovative concept without risk of liability.

But sometimes your budget leaves no other options.

For example, if the profits earned from the sales of products that implement your company’s innovative concept will likely total less than roughly $10,000 per year, it probably makes little sense to engage a patent attorney to prepare and prosecute an application that claims that concept. And perhaps it makes no sense to pursue a patent at all. What would you do with such a patent? Is there a substantial likelihood that infringers will try to “steal” that paltry pile of profits? What would it cost to obtain a court order commanding them to stop infringing, or mandating that they pay you for the profits you lost due to their infringement and/or for the royalties you would have earned if they had sought a license from you?

On the other hand, if the profits likely will total over $100,000 per year, then not only might patenting make sense for protecting that profit stream, but use of a competent patent attorney to prepare and submit the application is probably also fully justified. For likely profit values within this $10,000 to $100,000 range, it probably would be very beneficial to make your patenting decision after considering the Risk-Adjusted REturn (“RARE”) of the investment.

In any event, if patenting seems like the right approach, but the budget demands self-help (rather than professional help), then at least read and heed “Patent It Yourself” by David Pressman, which its publisher, Nolo Press, declares to be the “world’s bestselling patent book”. And finally, good luck.

I refer to an innovator’s detailed written description of their innovation as an “innovation disclosure”.

A well-written innovation disclosure can form a solid technical foundation for analyzing patentability, risks, and value, and help give your patent attorney what they need to craft a high-quality patent application.

It can be tempting for innovators to provide their patent attorney with a laundry list of trumpeted and fluffed-up attributes of their innovations and call it an innovation disclosure.

Unfortunately, such platitudes, while fine for sales and marketing efforts, usually don’t provide a patent attorney with the relevant information required to build a high-quality patent application.

Instead, at a minimum, a reasonable innovation disclosure will provide a:

It is probably safe to say that there are as many successful approaches to business development and product development as there are successful businesses and products on the market. Nevertheless, nearly every successful innovation sprouts from deep market research, i.e., deeply learning customers’ problems and needs, then relentlessly developing, market testing, and refining solutions to a selected problem until the innovator arrives at the single best solution to that problem.

Beyond that, because my primary expertise is in patent and intellectual property law, I generally limit myself to pointing to potential resources that might be able assist you with developing your business and product.

As you seek assistance, beware that there are a number of unscrupulous Invention Promoters (a.k.a. Invention Marketers, Invention Brokers, etc.) that are generally known for high-pressure sales techniques, misrepresentations, and even fraud. Please use caution before proceeding with anyone who seems to fit this description.

Although I don’t vouch for them or their advice, here are links to several potentially valuable resources that have earned relatively high ratings on Amazon:

“Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future” by Peter Thiel and Blake Masters, ASIN B00J6YBOFQ, 2014.

“Starting a Business QuickStart Guide: The Simplified Beginner’s Guide to Launching a Successful Small Business, Turning Your Vision into Reality, and Achieving Your Entrepreneurial Dream” by Ken Colwell, ASIN B07P1QTM2P, 2019.

“Build a Business, Not a Job: Grow Your Business & Get Your Life Back” by David Finkel and Stephanie Harkness, ASIN B0733J5S65, 2017.

“Crowdfunded: The Proven Path To Bring Your Product Idea To Life” by Mark Percota, ASIN B0CDFJKS72, 2023.

Although litigation is often a fact of life for bigger companies, companies of all sizes tend to experience a bit of disgust at the idea of being threatened with a patent infringement lawsuit. And nearly all companies would greatly prefer to never have to fight such a suit.

Avoiding patent infringement suits starts with avoiding infringement. And fortunately, there are many paths to avoiding infringement, including:

No matter what type of intellectual property rights are involved, I can assist with each of these activities, which also can apply to other types of intellectual property, such as trade secrets, marks, and copyrights.

In the patent realm, professional searches can lay the groundwork for avoiding and/or resolving many potential infringement disputes. For example, identifying what patent rights are owned by others is the objective of a patent clearance search and opinion. Determining what another’s patent rights cover, and whether those rights are infringed is the goal of a non-infringement search and opinion. And assessing the validity of another’s potentially infringed patent rights is the aim of a validity search and opinion.

Typically, a formal non-infringement opinion for a single U.S. patent costs in the range of US $5,000 to $10,000 (and sometimes considerably more) to prepare. That cost can depend on numerous factors, such as the:

A few of these factors can be determined readily before beginning the investigation, but most require considerable research to assess.

When there are many related patents, there sometimes can be a single non-infringement “theory” or basis that applies to most or all of the claims, thereby greatly reducing the overall cost (i.e., the costs could be much less than $5,000 to $10,000 multiplied by the number of patents). This possibility can only be determined upon deeply researching each patent in the group.

Keep in mind that tremendous funds potentially can be saved via obtaining an informal opinion formed upon a more brief/shallow investigation and assessment (undertaken on an hourly basis with a potential cap on costs). Such an informal opinion would not be provided in writing and would not be capable of serving as a defense against an allegation of willful infringement, but potentially would be very helpful in guiding strategy and the decision to seek a formal opinion, as well as estimating the cost of a formal opinion.

Once your company has obtained an appropriate and professional search and opinion, they might want to negotiate with the owner of the IP rights. Yet negotiating why another’s IP rights are invalid or not infringed can be a delicate exercise, which might evaporate the litigation threat, transform it into a lucrative business deal, or escalate hostilities substantially.

So sometimes, it simply can be easier to avoid another’s IP rights altogether, possibly by initially designing around, or later re-designing the potentially infringing product or service. Based on my legal understanding of the potentially infringed rights and my technical capabilities, I help my clients find successful design-arounds and re-designs.

In other situations, it can make good business sense to obtain authorization to practice another’s IP rights, such as via obtaining an assignment of, or license to, those rights. I have deep experience in negotiating and preparing such agreements.

The variety of potential business agreements involving intellectual assets and/or the property rights in such assets is simply astounding. Nevertheless, certain business scenarios appear with such frequency that tools and rules of thumb for crafting relevant agreements have emerged that often can smooth the way and avoid many potential pitfalls.

Perhaps the most common scenario is the need to disclose confidential information (which might be a trade secret) to someone outside the control of your company. In this situation, a Confidentiality or Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) is frequently relied upon. Key to many such agreements can be a clear identification of what confidential information must be kept secret, and what uses are allowable for that information. Other strategic considerations include requiring the disclosing party to mark all written materials as “confidential” and to summarize all confidential information disclosed verbally within a specific time frame after disclosure.

Closely related is the Employment Agreement (and its cousin, the Consulting Agreement). These agreements typically include confidentiality provisions, as well as requirements for assignment of intellectual property rights, assistance with obtaining and protecting intellectual property rights, and possibly a non-compete and/or non-solicitation clause.

Assignment clauses can require that founders, employees, contractors, and/or business partners assign their intellectual property rights to your company. Yet difficulties can emerge when, for example, the resulting assignment documents are drafted incorrectly, sought at the wrong time, or recorded improperly.

When entities agree to work together to research and/or develop technologies and/or products, they typically enter a Joint Development Agreement, which, in addition to the provisions described above, usually spells-out how jointly created innovations, discoveries, and information will be owned and handled.

Once an entity obtains intellectual property rights, it can retain those rights, yet authorize others to exploit some of them, via a Licensing Agreement (or “License Agreement”). The terms of such agreements can vary substantially depending on, for example, business needs, the type of intellectual property involved, the specific rights licensed, and/or the industry. An “exclusive” license allows only a single licensee to exploit the identified right, while a “non-exclusive” license allows each of multiple licensees to do so.

Disputes can arise, for example, in the process of negotiating an agreement involving intellectual property rights, or after such an agreement is in place. Yet careful agreement drafting, and reliance on professional dispute resolution techniques, can avoid litigation while preserving the business relationship and maximizing the value of the intellectual property rights.

Well before infringement of a patent is suspected, it can be worthwhile to verify that adequate financial resources will be available to finance enforcement of the rights to exclude others from practicing the patent. For those who do not have the financial means to engage in patent litigation, patent assertion insurance can be purchased that will provide the needed financial muscle to discourage or halt infringement.

When infringement is suspected, proceed extremely carefully to: